Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links to handpicked partners, including tours, gear and booking sites. If you click through or buy something via one of them, I may receive a small commission. This is at no extra cost to you and allows this site to keep running.

Seeing Orangutans in Borneo is a must. But the future of Semenggoh Centre, Sarawak is more about the tourists who visit and act recklessly.

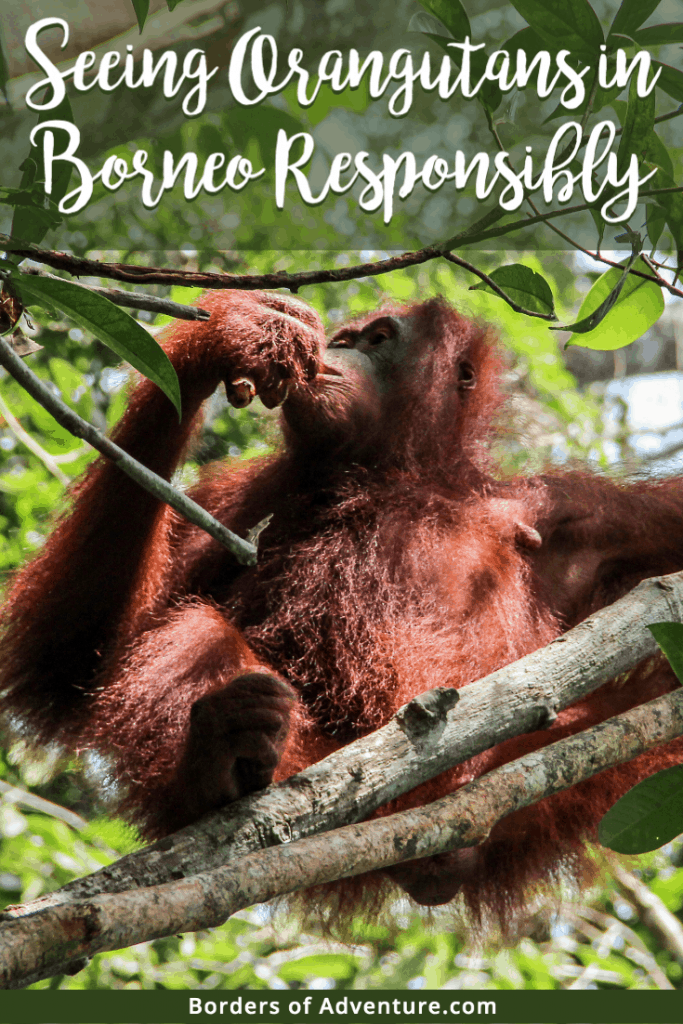

The opportunity to see orangutans in Borneo is an insatiable need when visiting this region. The Borneo orangutan is an endangered species that’s native only to the island and parts of Indonesia.

Aside from national park trekking and mountain climbing, it was one of the main things I wanted to do there. After all, many take holidays to Borneo to see orangutans as their main option since this is the place to get up close and personal to some of the world’s most incredible creatures without the restriction of a confined, zoo environment.

Orangutan Sanctuaries in Borneo (or Rehabilitation Centres as they are referred to) have become the most desirable option for seeing these native animals since a sighting is almost guaranteed in comparison to a trek through the wilderness of a National Park. The centres are set within an Orangutans natural habitat and effort is made to ensure that the forest area is maintained and not destroyed.

Contents

Best Place for Seeing Orangutans in Borneo

The island of Borneo is split into two states – Sarawak in the west and Sabah in the east – and each has its own orangutan sanctuary. The majority of people who visit Borneo stay mainly in one state rather than travel around, so that normally determines which centre you end up going to.

In Sarawak, there is the Semenggoh Wildlife Centre.

In Sabah, there is the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre.

Similar in their efforts, there’s still a divide regarding which is best. While the sanctuary in Sepilok is more popular, I choose to visit Semenggoh because I had heard from wildlife enthusiasts and other travellers that it was the better of the two. You can’t touch the orangutans, hold them or get that close as you potentially can in Sepilok (or so it’s said) – you are merely there to observe from a safe distance.

However, the notion of these centres has raised the debate regarding the accessibility of the animals and the resulting actions of the visitors, which I witnessed myself during my visit to Sarawak.

Orangutan Rehabilitation and Tourist Actions

The Semenggoh Wildlife Centre in Sarawak has been around for 40 years and helps to care predominately for orangutans who have been displaced, rescued from an inhumane environment (such as being kept as pets) or found injured in the forest.

Here they are taught to adapt to and live in the wild expanse of a forest reserve that is monitored and controlled. While many are never able to be released to the wild again, there is the possibility for it to happen if it could work.

The Semenggoh Wildlife Centre in Sarawak in Orangutans

However, the debate is that this constructed environment had led to the ‘humanisation’ of the animals, which in turn means they rely on humans too much and in turn are affected by the over-contact with them.

From my experience there, we should not be too quick to blame the centres themselves which house these incredible creatures, but the tourists on Borneo holidays who book an Orangutan tour, act disgracefully and ignore rules. The tourists who miss the point that an orangutan is a WILD animal.

Yet when I was there some visitors chose to ignore this point. In an environment where the orangutans are cared for in the most natural surroundings possible; where there are no cages, no glass windows and nothing to separate them and you from absolute, direct contact.

These actions are detrimental to the exact reasons this environment needs to exist – for protection.

Not only can getting too close to the animals confuse them, but the spread of human diseases is also likely.

Orangutans Feeding Time and the Viewing Frenzy

In Semenggoh, the 9 am feeding time meant that a large crowd had gathered for the special opportunity to see an orang-utan up close, and it really was – when a mother and her baby emerged from the undergrowth it really was a rare sight to behold. It made me stop in my tracks, edging a little closer slowly and softly to savour the precious moment.

For once, I didn’t have to squint through the trees, scramble for a pair of binoculars or rely on my camera’s zoom lens. Less than two metres away was a wild, beautiful, endangered animal, wandering slowly through the forest towards those who shared her land, without a care in the world.

When the mother and baby orangutans moved closer towards the crowd, we are politely asked by the park ranger to move back to give them the space they would normally be afforded in the wild.

An environment where human contact wouldn’t even exist.

Except the vast majority DIDN’T move back, waiting for that moment that the orang-utan would get just that little bit closer. At this point, the Park Ranger stood on his little platform to announce anxiously to the crowd that it was essential to give the orangutan space since she was about to cross the paved path to get to the other side of the forest.

Some people do adhere to the rules

He explained the definition of wild and how the orangutans live here. He declared that if the orangutan acts in self-defense, the park would NOT be liable since it would attack if threatened.

Especially the alpha male. You don’t in any way mess with the alpha male.

But did that stop anyone? No. It made me really anxious that something would happen, even if I did secretly want an orangutan to act to prove a point. The park rangers can only do so much when it comes to moving people, and it appears to be a pretty tough job.

For those of us who did move back, our view was obstructed by those crowding around the animal as she made her pass to the other side. The click, click of the cameras despite the warnings of using flash; the exasperating gasps, oohs and ahhs, despite the call for silence and space.

Tourists getting too close to Orangutans

How would you feel if a huge crowd of people descended on you like that? Yes, I would want to claw your face off too.

Seeing Orangutans in Borneo is a Unique Experience

Despite the actions of others, I wouldn’t think twice about visiting a place like this.

It exists for a positive purpose and it’s obvious that the park rangers have a close bond with the animals.

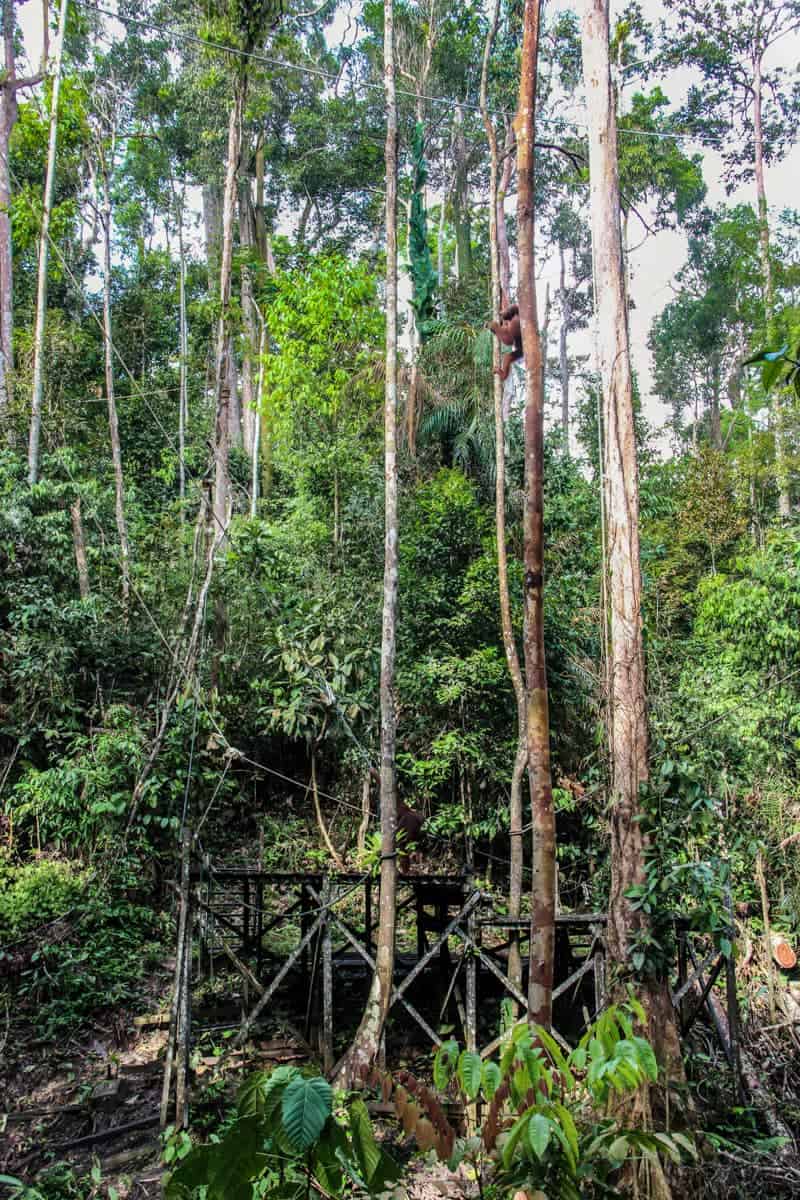

Overall, the orangutans appeared happy, content and playful. They are taught to fend for themselves and forage for food, as well as how to move through the jungle – with the aid of rope which you can see connected to the trees in the distance.

It was fascinating to see how frustrated one orangutan became at not being able to break open a coconut on his first few attempts! He’s here to learn after all.

For the more confident orangutans (and no doubt more inquisitive) who would appear from a branch right above you, a park ranger was always close by to appease the crowd or walk alongside the orangutan for the ultimate protection of all in the park – the orangutan leading the way and taking control.

In fact, tourists only have access to a very small part of the sanctuary forest area. With only two viewing platforms here, the rest of the dense forest is untouchable.

This is exactly how it should be in order for these animals to thrive in a natural environment, even if it has been constructed for them.

I’m glad I spent an hour observing these beautiful creatures and being able to be so close to them in a well-maintained and natural environment. It’s just a shame I didn’t enjoy observing my fellow man.

Think About Your Actions When you Visit Orangutan Centres

While the notion of a rehabilitation centre is debatable, there is praise for its existence.

Whilst visiting a National Park results in a greater need to protect it so that people can still visit, the destruction of an orangutan’s natural habitat poses a far greater threat than tourists observing them from a constructed viewing space.

It’s just a shame that some of us ruin that new environment in which Oranutans are now living.

Visiting Semenggoh Wildlife Centre, Sarawak

- The Semenggoh Wildlife Centre is approximately one hour from Kuching city centre by bus (2 Ringgit) and taxi (approximately 30 Ringgit). Staying in the city? Here’s what to do in Kuching to make the most of your time in Sarawak.

- The entrance permits cost 10 Malaysian Ringgit (€2-3) for adults and 5 Ringgit for children.

- Tickets can only be purchased at the entrance and not booked online or in advance.

- Opening times are 8 am to 10 am and 2 pm to 4 pm.

- This corresponds with feeding times that take place from 9 am to 10 am and 3 pm to 4 pm

- More information can be found on the official Semenggoh Wildlife Centre website.

Many thanks to The Sarawak Tourist Board who arranged my visit to the centre. All opinions, as always, are my own.

Becki says

I was there in 2012. I am sure this issue still exists, as it always has.

Jessika says

You are such a wonderful traveler. The way you weave your travel story is commendable. Great work!

Alexie says

Interesting post and I do agree that it is a pity to stumble across disrespectful tourists. While I haven’t been on the Malaysian side of Borneo, I did get to experience a rehabilitation center in Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo). The famous Camp Leaky was definitely one of the best experiences of my life; those same rules still applied and luckily our guide was making sure those rules were enforced. However, other guides did not insist as much and some tourists did seek physical contact with the orangutans. This being said, the guides and park rangers must really ensure those rules are being followed for the well-being of the animals.

Bec says

There definitely is a fine line between helping and harming when it comes to human interaction with wild animals. I haven’t been to Borneo yet, I will be there in 2 months time and can’t help but think the ignorance of tourists in such places is likely to put a dampener on such a wonderful experience (like you’ve said in other comments, lets hope I get well behaved humans on my visit!). Thanks for writing such a well-balanced and truthful post, fingers crossed this can educate a few people on how to act in these places for the good of the animals!

Stepahie Gregories Donaldson says

I saw a programme where Julia Roberts had very close physical contact with many orangutangs including babies. Why was she able to endanger these animals by exposing them to disease? My understanding is that all humans are forbidden to touch these animals. Does that rule not apply to movie stars?

Becki says

The rules should apply, yes. Unless she was heavily screened beforehand. The park keepers are the only people who should and do have close contact with them.

Kristin Addis says

I’m in Borneo now and trying to find something less touristy as a way to view them. Do you know of anywhere that you can view them, from a distance, where they naturally live? The photos of all the tourists turned me off!

Becki says

This place is natural – you just have to hope you don’t get the bad tourists!

Glamourous Traveller says

Great point. I really love Semenggoh because they try to keep things as ‘natural’ as possible. If it makes you feel better, I’ve been there twice, and the first time I saw nothing because it was fruit season and the orang utan’s were off foraging in the forest. The second time we went into the podium area to watch the alpha male come swinging down from somewhere in the middle of the jungle. An amazing site.

And to those tourists who didnt listen to guides to keep quiet? Yep, they got peed on by some baby orang utan’s who were travelling over our heads unaware.

Monica says

It’s such a shame that there are always people that seem to ruin it for everyone.

I went to Sepilok about 2 years ago and, thankfully, I didn’t see any behaviour like this. I also didn’t see anything that would suggest you can touch or hold the orangutans. They were worryingly tame and would come quite close but I didn’t see any people trying to get too close. I was really surprised at Sepilok how peaceful it was. It really was like entering a sanctuary.

Great pics btw!

Becki says

I’ve heard that in Sepilok now you can get really close as they are more humanised. I choose not to go to both as I thought they would be very similar. Such beaufiful surroundings though!

Maddie says

Wow, quite shocking that people would behave like that. We desperately wanted to see orang-utans and after weighing up the options decided on the Sumatran jungle, it looks like we made the right choice. I believe there is definitely a place for rehabilitation centres, especially due to how orang-utans are dealt with by plantation owners but there should be tighter regulations on how tourists interact with them.

Becki says

I agree, the rehabilitation centres are a good thing and the rangers work hard to set the rules. I guess there just needs to be more enforcement now. Limiting numbers? Yet that decreases income for the programmes. I’d like to see more rangers assigned to smaller groups of people – almost monitoring them. But that means more expenditure for staff that could be spent on the rehabilitation programmes. A tricky subject indeed…

Arianwen says

Another well-balanced viewpoint. I think it’s great that you consider the pros and cons of everywhere you go and act to promote sustainable tourism. I can see why people get over excited at a place like this, but it looks from the photos like a lot of them aren’t paying much attention to the rules or considering what’s in the animals’ best interests.