Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links to handpicked partners, including tours, gear and booking sites. If you click through or buy something via one of them, I may receive a small commission. This is at no extra cost to you and allows this site to keep running.

While the South Styrian winegrowing region is renowned for its viniculture heritage, the Styrian capital, Graz, has revived a 12th-century history of urban wine production that ended in the 1960s.

In Austria, it’s not just Vienna that can claim to be a capital growing wine within its city limits. On the slopes of Graz’s western Kehlberg hill overlooking the Styrian capital city, a tour of a vineyard owned by wine grower Gabi Blaschitz and her family tells a different story. “There’s a ridge by the house called ‘Am Weinhang’, which means ‘at the vineyard’ – a hint that wine has been growing here for ages,” says Gabi.

The Kehlberg, with its confluence of Mediterranean warmth, Alpine coolness and a rare dolomite terroir distinct from the famed South Styrian region, has always been a prime ground for winemaking. The vineyards, sloped on steep hills ensuring maximum sunlight exposure, contribute to the unique minerality and flavour profiles of the wines. This topography necessitates a strenuous harvest carried out almost entirely by hand.

On the Kehlberg hill, where Graz city wine is cultivated.

Contents

The History of Graz Wine

The heirloom of Graz wineries paused in the 1960s after a 900-year history. The Blaschitz family were offered the grounds after a neighbour asked them to rebuild the former vineyard area. “We found documents that wine has been growing here since 1124,” Gabi tells us as we wander through woodland dotted with ancient stone walls before entering the relic of an old house with a wine press and browsing a Buschenschank wine menu from 1925.

The relic of the old winemaking house still standing at the vineyard in a nod to the area’s history.

The last harvest of 1967, before the Falter Ego label brought back Graz city wine production.

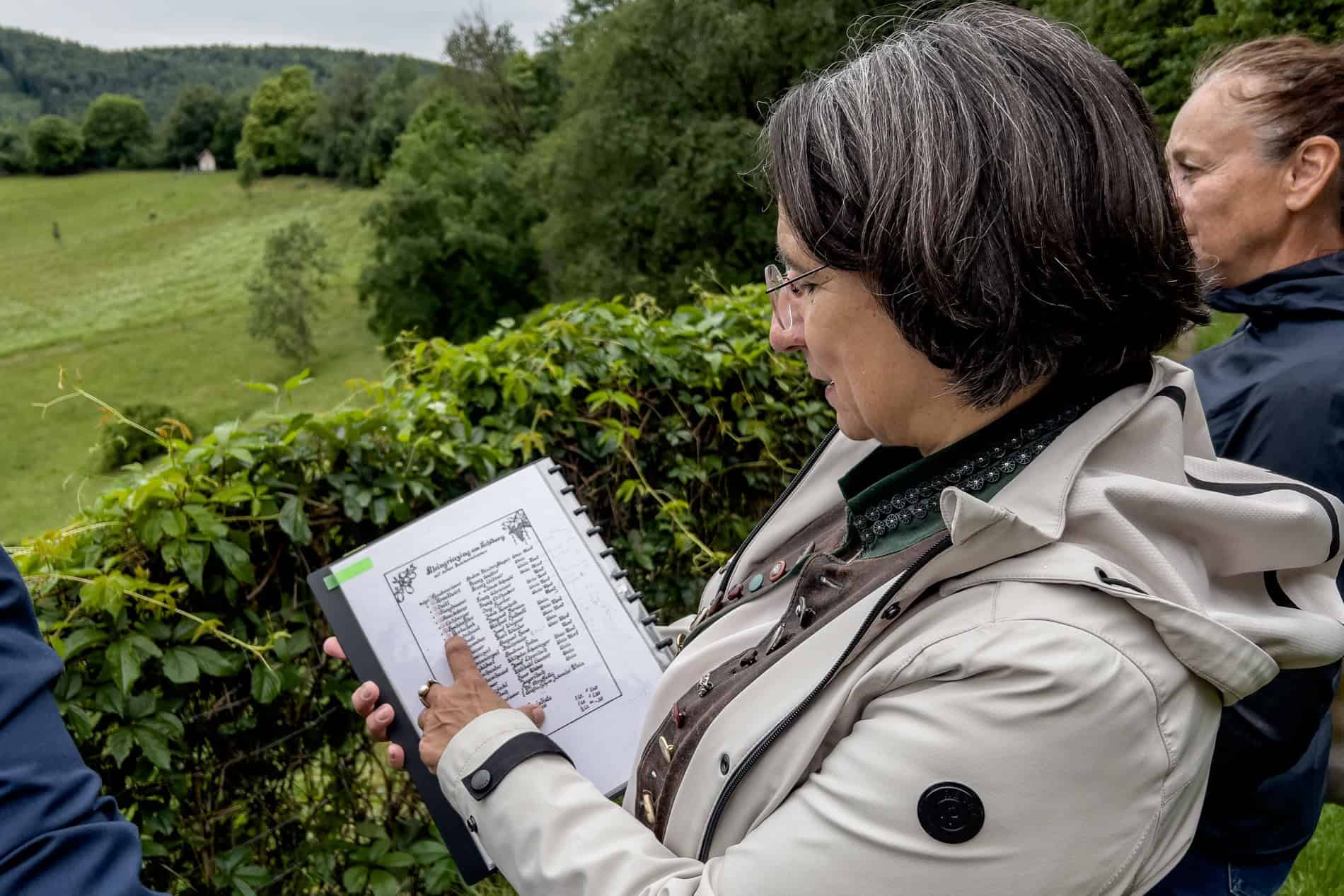

Gabi Blaschitz shows the Buschenschank wine menu from 1925. There were once 21 wine taverns in this area.

At its peak, the Graz wine region covered almost 200 hectares with 21 wine taverns, earning it the nickname “Klein-Grinzing” (small Grinzing) —named after the most well-known wine village in Vienna’s northern 19th district urban vineyard fringes. However, by 1967, the last wine tavern had closed, marking the end of an era.

Wine production was disrupted post-World War II when the industrialisation of beer and the influx of cheaper wines from Italy and Hungary led to a decline in local production. The Austrian wine scandal in 1986 decimated the industry.

However, this crisis proved to be a turning point. The new generation of winemakers, armed with international experience and rigorous standards, revitalised the industry. Today in Styria, any vineyard with more than 500 plants must adhere to strict laws regarding steepness and south-facing vine direction. The three Styrian DAC regions mandate hand harvesting to preserve cultural heritage.

The Falter Ego wine, made from the grapes harvested on Kehlberg, is a collaboration that began in 2013, giving the Graz vineyard a new life. “Normally, you have wine grown in the landscape of Southern Styria or Vulkanland, but our wine is growing within the city limits of Graz. And with Hannes, we have one of the best winemakers in Austria,” Gabi proudly enthuses.

Not only does Falter Ego contribute to the city’s preservation of cultural heritage, but it also plays a role in environmental conservation, protecting the rare Easterluzei (Easter Lily) plant and its butterfly species, which inspired the name Falter Ego: “Falter” translates to butterfly in German.

The Falter Ego vineyard is accessible on a public hiking path.

The vineyard protects the rare Easterluzei (Easter Lily) plant and its butterfly species.

Wine tasting at the Blaschitz family hilltop, vineyard home.

The people behind Falter Ego: Winegrower Gabi Blaschitz with Winemaker, Hannes Sabbathi.

A Renowned Winemaker’s Vision

Renowned Winemaker Hannes Sabbathi, a fourth-generation vintner who produced his first vintage at 16 during his first year at the Silberberg wine school, has been instrumental in this revival. Styria is famous for fresh, crisp white wines cultivated on some 5,000 hectares of family-owned wineries renowned for high-quality production.

Although wine has been produced in the region since the Roman era, Hannes explains why he wants to focus on city vineyards and their unique terroir. “I am a fan of the different soils in our region that are 12-14 million years old. When I saw this soil you could not find in other places in Styria, I knew it was a unique style. It’s why I started this project: to show what is possible. Not many cities can say they have their own wine.”

Falter Ego’s first release was in 2018, with Sauvignon Blanc and Yellow Muscat. Grauburgunder Ried Kehlberg was released the following year.

Renowned Styrian Winemaker and fourth-generation vintner Hannes Sabbathi.

During a wine-tasting session, Hannes explains what makes Graz wines unique. “The USP of this wine region is we have a lot of rain. The French side of the Pyrenees has the most rainfall in Europe, with 2000 litres of rain annually. Next is Styria, with a minimum of 1200-1500 litres. We also have warm temperatures – 30-35 degrees for some weeks. It’s difficult for us to work in the vineyards, but for the plants, it is perfect. With the higher quality, late harvest, and more powerful wines, we get nice, fresh acidity.”

Sabathi’s commitment to showcasing the terroir is evident in the wines produced. Falter Ego’s Sauvignon Blanc constitutes 50% of its production and the 2022 Stadtblick “city view” wine is a Sauvignon Blanc regional blend that embodies the area’s fresh and varietal style. “The region was renowned for this style of wine. It’s the work of the last 30, 40 years,” explains Hannes.

We compare it with the 2021 vintage, which Hannes adds “is one of the biggest vintages in Austria, with more deepness, higher ripeness and can age for the next 10-15 years.” The Gelber Muskateller is known for its light and refreshing profile, which we are told pairs perfectly with local dishes like the Styrian Backhendl (fried chicken) and light cheeses. The Ried Kehlberg wines are made differently, fermented over 2.5 years in 500-litre barrels. “The idea is to show how you can work with it like a red wine – bigger glasses, warmer temperatures, and ideal for heavy dishes.”

Falter Ego’s Sauvignon Blanc constitutes 50% of its production.

Graz Locals and the Passion of Preservation

Emphasising the city’s strong connection between food and wine, the primary market for Falter Ego wine is Graz restaurants — a given in a city whose gastronomic endeavours have earned the Culinary Capital of Austria title.

“Graz is a city not just for sightseeing but for food and wine. Restaurants are very happy to have it on the wine list,” Hannes adds as we discuss the proximity of Styria’s wine regions, the long-standing heritage of buying wines direct from the vintner, and the continued rise in bookings of at-the-vineyard wine holidays, as the South Styrian Wine Road is known for.

The renaissance of city wine has put the urban Buschenshank offering back on the menu and Graz on the regional wine map. With every sip, you can taste the dedication to sustainability at the hands of passionate locals like Gabi and Hannes, who are bottling Graz’s legacy from vine to glass.

The renaissance of city wine started here in western Graz, reviving a 12th-century tradition.

Visiting the Sustainable City of Graz

From social enterprises and community initiatives to family-run hotels and cultural arts movements – modern-day Graz and the people who make it pave a model ideal for sustainable urbanism worldwide. These guides on everything from sightseeing to sustainability have you covered for a slow travel trip to the Styrian capital.

- Graz Sustainable City Tourism – Meeting the Makers

- Sightseeing in Graz – What to See in the Mediterranean City of Austria

- Day Trips from Graz – Art, Culture and Nature Accessible from the City

This article is in partnership with Graz Tourism, following a trip to meet the local people who contribute to the city’s preservation and development. All opinions about Graz as a sustainable city in Austria remain my own.

Leave a Reply